Tennis through the ages: Why Wimbledon moved

Stars such as Frenchwoman Suzanne Lenglen and American Bill Tilden meant the game’s popularity was growing, and in 1922 Wimbledon was forced to find new premises…

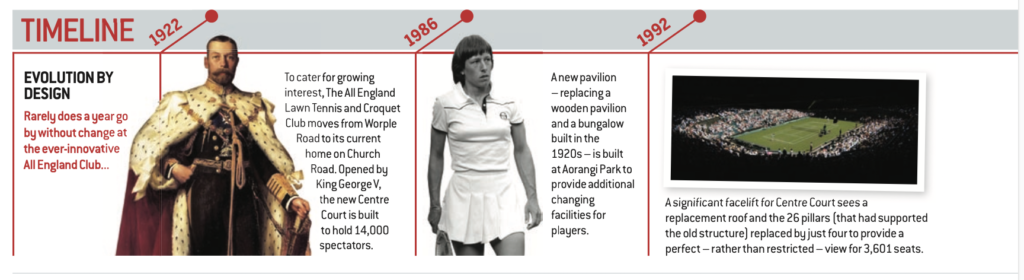

The years immediately after World War I saw a surge in spectator interest in tennis, and the construction of the great stadiums that would host the four Grand Slam tournaments for most of the 20th century. In 1922 Wimbledon moved to new, bigger grounds at Church Road, with a purpose-built 13,500-capacity Centre Court arena – designed by architect Captain Stanley Peach – and another 12 outside courts. The post-war years also saw the opening of the world’s other great tennis stadiums: White City, Sydney (1922), Forest Hills in New York (1923), Roland Garros (1928) and Kooyong in Melbourne (1932). These venues would host the four Grand Slam events for most of the 20th century.

Some 200 spectators had watched the first Wimbledon men’s final in 1877, but by 1913 10,000 people were inside the grounds on the second Friday of the Championships for the Gentlemen’s Challenge Round match when defending champion Anthony Wilding beat Maurice McLaughlin – the “California Comet”–in three straight but closely-contested sets. Improvements in communications along with the arrival of charismatic stars like dashing New Zealander Wilding had created a huge public demand which Wimbledon’s Worple Road ground was simply too small to satisfy. Surrounded on three sides by residential streets and on the fourth by the London and South Western Railway, there was no room for expansion. The onset of World War I in 1914 delayed Wimbledon’s decision, but when peace was restored in 1919, the long-awaited debut of Suzanne Lenglen–France’s famous Divadu Tenis – made a move to new premises more pressing. The arrival a year later of the charismatic American champion Bill Tilden made such a change inevitable.

In May 1914, 15-year-old Lenglen was beaten in the final of the French Championships by her compatriot Mlle Broquedis in a tight three- set match. Incredibly, this was to be the last defeat of her career. For the next 12 years until she turned professional in 1926, the Frenchwoman went undefeated in singles play. She was never beaten in singles at Wimbledon, and between 1919 and 1925, she won a total of 15 Wimbledon titles, including six in singles. She also won 19 French Championships, again including six in singles, and two Olympic gold medals. This extraordinary record places her above all other women in the history of the game.

Born in Paris in 1899, the young Suzanne spent her winters in Nice on the French Riviera, in a family home facing the Nice Lawn Tennis Club. Her father Charles gave Suzanne her first tennis racket when she was 11, a very young age in which to start the game in those days, and she immediately showed great promise. Tennis was an important part of the Riviera’s social season, and from January to April each year a number of tournaments took place in Nice, Cannes, Beaulieu,MentonandMonteCarlo. Inher teenage years she enjoyed great success in these events, first in the handicap draws and later in the open adult events.

During her years as the world’s undisputed No.1, she continued to play the Riviera circuit, and in February 1926 the Carlton Club at Cannes was the scene of a memorable match when Suzanne at last came head-to-head with America’s emerging star Helen Wills. The 20-year old Californian had just won her third consecutive US singles title, and many pundits believed that she would be the player to at last end Suzanne’s 12-year unbeaten run. There was a huge clamour for tickets for the match, and even the erection of a large temporary stand – doubling the usual seating capacity to 3,000 – could not satisfy the demand. Suzanne won the match 6-3 8-6 but the young Wills had done enough to show that she was the rightful heir to the Frenchwoman’s crown. Later that year, Suzanne won the French singles title for a sixth time, but defaulted at Wimbledon due to injury. Earlier in the tournament she had been at the centre of a controversy when the Queen had arrived at Wimbledon expecting to see her play, only for Suzanne to be absent due to a breakdown in communications. Some members of the Centre Court crowd turned against Lenglen, who left Wimbledon under a cloud, never to return. She turned professional a few weeks later and sadly died in Paris in 1938, aged just 39.

Despite her early death, Lenglen had single-handedly elevated lawn tennis from the sports pages to front-page headline news. She swept aside old Victorian values of dress and decorum, playing with a graceful, athletic style in daring outfits that revealed far more female flesh than had ever been seen in public before. She was charismatic, enigmatic, and a fashion icon; the first global superstar in women’s sports.

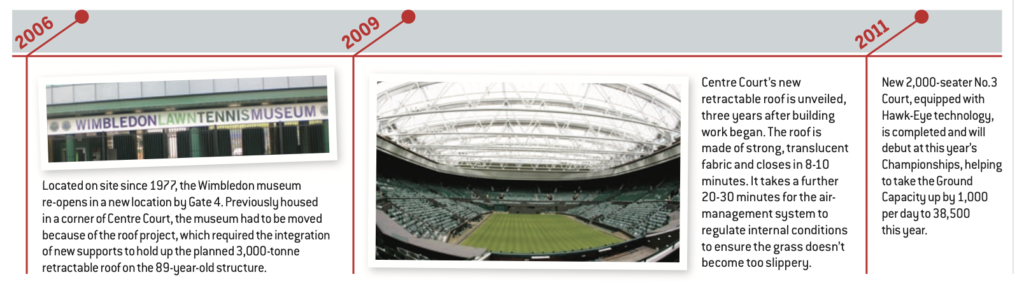

Located on site since 1977, the Wimbledon museum re-opens in a new location by Gate 4. Previously housed in a corner of Centre Court, the museum had to be moved because of the roof project, which required the integration of new supports to hold up the planned 3,000-tonne retractable roof on the 89-year-old structure.

In men’s tennis, the post-war years saw a fascinating battle for supremacy between Frenchmen Jean Borotra, Rene Lacoste (founder of the Lacoste clothing brand), Henri Cochet and Toto Brugnon – collectively known as The Four Musketeers – along with America’s Big Bill Tilden. Tilden was a larger than life character who many believe to be the greatest player of all time. He won his first Wimbledon singles title in 1920 at the age of 27, and his third and last ten years later at 37, making him Wimbledon’s second-oldest singles champion. Tilden was no stranger to controversy. As a champion in the amateur era he was constantly at odds with officialdom over his off-court earnings from writing and journalism, and in later life he served a term in jail for a sexual offence. Tilden continued to play high-level competitive tennis up to his death in 1953 at the age of 60.

As the 1920s drew to a close, tennis – like other major sports – remained high profile as people sought to shut out thoughts of the world’s growing economic and political uncertainties. The first radio broadcasts from Wimbledon in 1927 created even wider interest in The Championships, and it seemed that whatever problems might beset the outside world, tennis in general and Wimbledon in particular were destined to go from strength to strength.

This feature was orignally published in Tennishead magazine back in 2007 and you can grab your own annual subscription, which includes 4 stunning printed magazine editions and 24 issues of The Bagel newsletter.

![]() Join >> Receive $700/£600 of tennis gear from the Tennishead CLUB

Join >> Receive $700/£600 of tennis gear from the Tennishead CLUB

![]() Social >> Facebook, Twitter & YouTube

Social >> Facebook, Twitter & YouTube

![]() Read >> World’s best tennis magazine

Read >> World’s best tennis magazine

![]() Shop >> Lowest price tennis gear from our trusted partner

Shop >> Lowest price tennis gear from our trusted partner